Fouling tested for better chemicals

New methods could allow the chemical industry to make better use of water.

New methods could allow the chemical industry to make better use of water.

Researchers at Curtin University have uncovered a novel approach that could significantly reduce the environmental footprint of the global chemical industry, a major consumer of fossil fuels and a significant contributor to climate change.

The chemical industry, pivotal in the production of everything from plastics to pharmaceuticals, has long faced challenges with processes involving organic materials and electricity.

These organic compounds do not dissolve well in water, typically requiring the use of fossil fuels to generate the necessary reactions.

This method not only increases the carbon footprint of the industry but also introduces additional safety and environmental risks due to the flammable and often toxic nature of the solvents involved.

However, a process known as “fouling” could enhance the efficiency of these reactions.

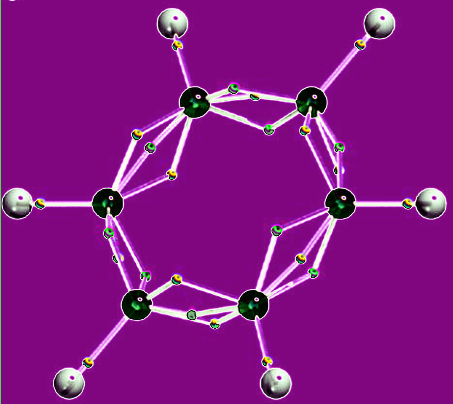

Somewhat counterintuitively, Associate Professor Simone Ciampi’s team discovered that adding water-resistant materials, such as plastics or oils, to an electrode can accelerate chemical reactions significantly.

“Fouling goes completely against conventional wisdom, which says you have to have clean instruments to make processes using an electrode as efficient as possible,” Professor Ciampi said.

The research team’s tests showed reactions occurring up to six times faster in fouled areas compared to clean areas of the electrode.

The researchers even found that common household glue could increase reaction speeds by 22 per cent, highlighting the potential for everyday materials to contribute to more sustainable industrial processes.

The organic materials in question are attracted to other hydrophobic (water-resistant) materials, as explained by Harry Rodriguez, a PhD candidate and study co-lead.

“If the material is hydrophobic – which means it does not like water – it will want to get out, so it will be drawn to a hydrophobic environment such as oil, plastic, or glue on an electrode,” Rodriguez says.

This finding is particularly relevant as the chemical industry has been keen to shift towards using water, despite poor yields with current technologies.

The use of water can mitigate many of the environmental and safety risks associated with traditional solvents.

“But companies still want to use water if it’s viable, because the chemicals they currently use for these reactions are expensive and flammable, so there are concerns and potential complications over safety and storage,” Rodriguez said.

While the fouling method offers promising results, scaling it up to industry-level applications will require further research and collaboration across different sectors.

Professor Ciampi suggested that partnering with industries like mining, which routinely use similar techniques, could expedite this process.

“There’s a wealth of knowledge out there which could be paired with electrochemistry to bring this method up to a bigger scale and then have a real impact,” Ciampi said.

The paper, ‘Insulator-on-Conductor Fouling Amplifies Aqueous Electrolysis Rates’, has been published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Print

Print