Soft 'bot breaks states

Scientists have created a robot that can shift between liquid and solid states, not unlike a tiny T-1000 Terminator.

Scientists have created a robot that can shift between liquid and solid states, not unlike a tiny T-1000 Terminator.

Inspired by sea cucumbers, engineers have designed miniature robots that rapidly and reversibly shift between liquid and solid states.

On top of being able to shape-shift, the robots are magnetic and can conduct electricity. In recent tests, the researchers put the robots through an obstacle course of mobility and shape-morphing.

Where traditional robots are hard-bodied and stiff, “soft” robots have the opposite problem; they are flexible but weak, and their movements are difficult to control.

“Giving robots the ability to switch between liquid and solid states endows them with more functionality,” says Chengfeng Pan, an engineer at The Chinese University of Hong Kong who led the study.

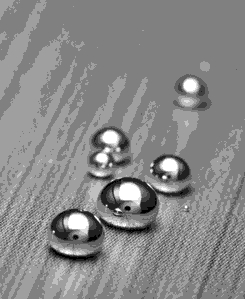

The team created the new phase-shifting material - dubbed a “magnetoactive solid-liquid phase transitional machine” - by embedding magnetic particles in gallium, a metal with a very low melting point (29.8 °C).

“The magnetic particles here have two roles,” says senior author and mechanical engineer Carmel Majidi (@SoftMachinesLab) of Carnegie Mellon University.

“One is that they make the material responsive to an alternating magnetic field, so you can, through induction, heat up the material and cause the phase change. But the magnetic particles also give the robots mobility and the ability to move in response to the magnetic field.”

Before exploring potential applications, the team tested the material’s mobility and strength in a variety of contexts.

With the aid of a magnetic field, the robots jumped over moats, climbed walls, and even split in half to cooperatively move other objects around before coalescing back together.

In one video, a robot shaped like a person liquifies to ooze through a grid before reforming its body.

“Now, we’re pushing this material system in more practical ways to solve some very specific medical and engineering problems,” says Dr Pan.

On the biomedical side, the team used the robots to remove a foreign object from a model stomach and to deliver drugs on-demand into the same stomach.

They have also demonstrated how the material could work as smart soldering robots for wireless circuit assembly and repair (by oozing into hard-to-reach circuits and acting as both solder and conductor) and as a universal mechanical “screw” for assembling parts in hard-to-reach spaces (by melting into the threaded screw socket and then solidifying; no actual screwing required.)

“Future work should further explore how these robots could be used within a biomedical context,” says Dr Majidi.

“What we're showing are just one-off demonstrations, proofs of concept, but much more study will be required to delve into how this could actually be used for drug delivery or for removing foreign objects.”

Print

Print