Asteroid smack successful

Australian scientists have assisted NASA in testing the first ever asteroid redirection.

Australian scientists have assisted NASA in testing the first ever asteroid redirection.

On Tuesday morning, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test spacecraft, or DART, slammed into a small asteroid, demonstrating technology that could protect Earth from a space rock in the future.

It was also the first time humans have altered the dynamics of a solar system body in a measurable way, according to the European Space Agency.

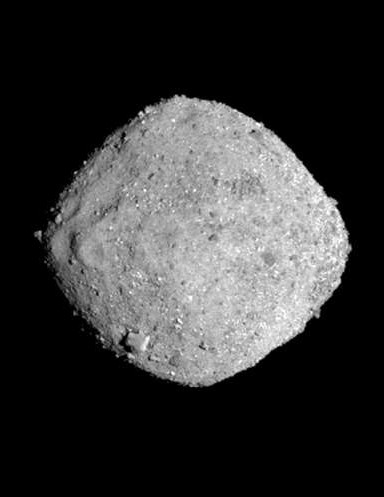

The target asteroid, Dimorphos, is 160 metres in diameter, roughly the size of the Great Pyramid of Giza, and orbits a larger companion asteroid, Didymos.

DART’s collision with Dimorphos should reduce the time it takes to orbit Didymos by a few minutes.

The DART spacecraft transmitted images back to Earth as it approached the asteroid, with the impact being monitored by a cubesat, LICIACube, which separated from DART.

From a safe distance, LICIACube’s cameras were able to record the impact, transmitting its pictures and other data back to Earth.

Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, manages the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (CDSCC), one of three stations around the world that make up NASA’s Deep Space Network.

CDSCC has supported the DART mission since its launch in November 2021 and received the final signals from the spacecraft as it approached and impacted asteroid Dimorphos. CDSCC will also receive images and data from the LICIA cubesat as it follows DART’s impact with the asteroid.

The European Space Agency’s New Norcia deep space tracking station in Western Australia, also managed by CSIRO, has been providing support to NASA’s Deep Space Network for the DART mission since May 2022.

During the final stages of the mission, the 35-metre antenna at New Norcia was able to receive data from the spacecraft that will be used by scientists to estimate the mass of the asteroid, surface type and impact site.

A few years after the impact, the European Space Agency’s Hera mission will conduct a follow-up investigation of Dimorphos, and the larger asteroid in the system, Didymos.

More images of the impact will be streamed back to Earth in the weeks and months following the collision from a satellite provided by the Italian Space Agency.

Ed Reynolds, the DART Project manager at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, described the mood inside the mission command centre just minutes before the historic impact.

“It was just joy,” he said in a press conference following the event.

Elena Adams, the DART mission systems engineer at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, said she was relieved it was over.

After more than 1,000 people working on DART for more than seven years, she said it is “absolutely wonderful to do something this amazing and we are so excited to be done”.

“To see it so beautifully concluded today was an incredible feeling,” she added.

Engineers of the DART mission expect images taken of the collision and the aftermath by a brief-case-sized CubeSat within the next coming days, but actual quantitative data on the impact of the mission will take about two months.

Three minutes after impact, LICIACube was to fly by Dimorphos to capture images and video of the impact plume and maybe even spy on the impact crater.

“So of course the ground base observatories are already taking data right now... but what we're probably going to see in the next couple of months, we're actually going to get confirmation of exact period change that we made. So it's not going to be tomorrow, I'm sorry, But we might see some LICIACube cube set images coming up the next day or two,” Dr Adams said.

The approach and impact can be seen in the video below.

Print

Print