New nanobots get target training

Bio-engineers have designed tiny nanobots made of DNA and protein that can target tumours to stop them from growing.

Bio-engineers have designed tiny nanobots made of DNA and protein that can target tumours to stop them from growing.

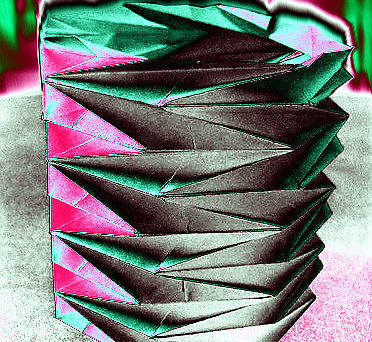

The nanobots are made using a technique called “DNA origami”, where specially constructed sheets of DNA were folded up and bound together to form a tube-like structure.

They are then embedded with the blood-clotting agent thrombin.

“Thrombin is a naturally-occurring protein that causes blood clots to form,” said Professor Greg Anderson, head of the Chronic Disorders Research Program at QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute.

“This ability can be harnessed to kill tumour cells by developing a system where the thrombin only causes clots in the blood vessels that are feeding the tumour, and not elsewhere in the body.

“When that happens, the tumour cells no longer receive essential nutrients and they die.”

The robots are designed so that thrombin is released only after it is ‘unlocked’ by a particular protein found within the blood vessels of tumours.

“The nanorobot keeps the clotting agent disguised until it reaches the place where we want it to act. In this case, that’s the tumour,” Dr Anderson said.

“That’s why this is such a clever delivery method.”

Professor Anderson said it was a highly-innovative example of nanotechnology being used to target tumours.

“This approach is novel in the way the team has combined a number of existing but different elements of nanotechnology to enable the controlled and targeted delivery of the blood-clotting agent,” he said.

“It shows just what is possible with contemporary biomedical technology and hints at what may be the future of intelligent drug delivery.

“Methods like this could potentially be used to deliver a wide range of drugs, and even multiple drugs at once.

“There are really limitless combinations of technologies and drugs that could be tried.

“The applications of the technology are certainly not restricted to tumour development, either.”

The targeted nanorobots also proved highly effective at reducing the growth and spread of tumours with characteristics of breast cancer and melanoma in mice.

Professor Anderson said although the treatment was successful in laboratory tests, it was still some time before the strategy would be tested in humans.

“It is an extremely exciting first step, but more work needs to be done,” he said.

“Nevertheless, the use of the DNA origami approach potentially provides a new tool that could be used to help achieve the ultimate goal of eradicating primary tumours and their metastases.”

Print

Print