New energy in puddle-power breakthrough

Bioengineers have created a fully functioning engine that runs on the evaporation of room-temperature water.

Bioengineers have created a fully functioning engine that runs on the evaporation of room-temperature water.

To build the world’s newest form of renewable energy, researchers at Columbia University designed a system that draws power from nothing more than a puddle of resting water.

In tests so far, puddle-power has been able to light an LED and even power a miniature car.

The engine harvests useful amounts of energy from the infinitely small and naturally occurring gradients in temperature on the surface of water.

These tiny temperature gradients exist everywhere, even in some of the most remote places on Earth.

The key to the exciting new invention is a new material called a ‘HYDRA’, short for hygroscopy-driven artificial muscles.

HYDRAs are thin, muscle-like plastic bands that expand and contract with changes in humidity.

A finger-length HYDRA band can contract and expand (almost quadruple its length) over a million times with virtually no degradation of the material.

HYDRAs use the naturally-occurring dormant spores of the common grass bacillus bacteria, which can soak up and exude ambient levels of evaporated water. Each time they do this, they expand and shrink considerably.

To make a functioning HYDRA, Columbia engineers painted the spores onto plastic strips using laboratory glue.

By covering a single strip on alternating sides with the dormant spores, their moisture-driven pulsating behaviour causes the plastic to flex and release in a single direction.

While it might seem that using a natural material would limit the lifespan of the engines, spores are known to survive in dormancy for decades or even hundreds of years.

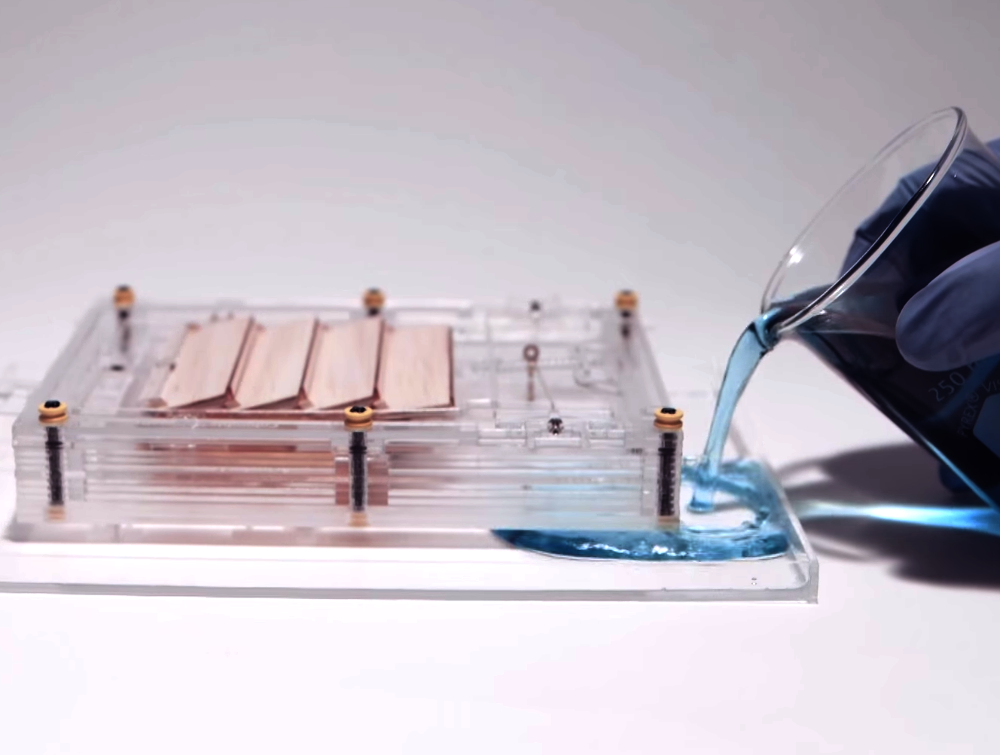

To use the stretchy HYDRA strips in a functioning engine, they were placed over a puddle of room-temperature water to form a small enclosure.

As the water on the surface naturally evaporates, the humidity in the chamber causes the HYDRAs to expand and pulling on a cord which is attached to a small electromagnetic generator.

The motion also pulls open a set of four shutters on top of the engine, which releases the humid air. This in turn causes the HYDRAs to shed their water-vapour and contract, pulling the shutters back closed. The process repeats over and over, like the cycle of a traditional engine.

The engine functions well at room temperature and even better as the water gets hotter.

The engine functions well at room temperature and even better as the water gets hotter.

With water at 15.5°C, the engine will open and close its shutters once every 40 seconds, at 21.2°C every 20 seconds, and at 32.2°C they open and close every 10 seconds.

The team has also tested a second engine design, which uses a turbine-style setup to make HYDRAs spin a wheel.

They attached it to the top of a miniature car, allowing the entire device to slowly eke forward powered only by evaporating water.

Each pull of the engine generates about 50 microwatts, so the HYDRA turbine will not be powering any houses just yet. But excitingly, the system has already been able to power an LED using only the energy of a resting puddle of water.

There is plenty of room for improvement too, given that each HYDRA band uses just 1 per cent of energy potential of the bacteria spores.

The Columbia University team is working on a new HYDRA base materials that could access another third of the spores' energy potential.

For now, the evaporation engine remains an intriguing proof of concept which shows that this unique type of energy generation really can be useful.

Bio-engineer and research leader Ozgur Sahin says there could be some incredible potential lying untapped around the world.

“The power in wind on a global scale primarily comes from evaporation,” Sahin told reporters, “so there's more power to be had here than there is in the wind”.

Print

Print