Local lasers boost hot knowledge

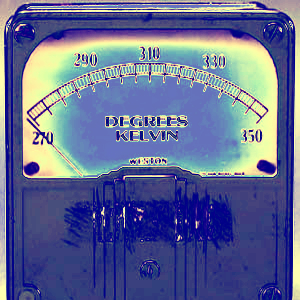

Australian scientists have produced a laser device that could create a new international standard for temperature.

Australian scientists have produced a laser device that could create a new international standard for temperature.

Researchers from the University of Adelaide, University of Queensland and University of Western Australia, have come up with a new way to determine Boltzmann’s constant - a number which relates the motion of individual atoms to their temperature.

The experiments contribute to a worldwide scientific effort to redefine the international unit of temperature: the kelvin.

“Although temperature is a familiar concept to all of us, remarkably it can only be measured accurately at a handful of locations around the globe,” says project leader, Professor Andre Luiten.

The researchers used lasers to make highly accurate measurements of the speed of individual atoms moving in a gas.

“An atom sitting at rest will absorb light of a particular frequency or colour ─ if it is moving towards you or away from you then the absorbed light is very slightly changed because of something called the Doppler effect,” Professor Luiten said.

“This is exactly the same effect that makes a police siren sound different depending on whether the car is moving towards you or away.

“We use a pure laser to measure these changes in light absorption, from which we can infer the speeds of the atoms and the temperature of the gas.”

By conducting the experiments with world-record precision the team came across a completely unexpected effect.

The light has an apparent effect on the atoms themselves: the measurement itself ends up changing the result. One of the breakthroughs of the project was to develop an explanation of how this happened and ensuring that it didn't affect the result.

The development means any laboratory in the world with appropriate skills and equipment could accurately measure temperature. Further development could deliver this capability to industry – something never before possible.

“Traditionally scientists kept a set of special clocks, rules and standard masses to define units such as the second, metre and kilogram,” says Associate Professor Tom Stace, from the University of Queensland.

“Over the last 50 years we have been getting rid of these standards and replacing them with universal quantities such as the speed of light or the frequency at which certain atoms vibrate.

“This program is completed for time, electrical quantities and length but mass and temperature still make use of special objects. In the case of temperature, it is based on the freezing point of a very special type of water to define the kelvin which makes it difficult for all laboratories around the world to agree about temperature.

“Our work will bring a universally agreed temperature scale to the globe. As with any upgrade, this one will be deemed successful if people hardly notice the transition on a day-to-day basis.

“But for those at the cutting edge -- whether developing new metal alloys at very high temperatures, or measuring the temperatures of the coldest substances, the need for absolute temperature is critical.”

Print

Print