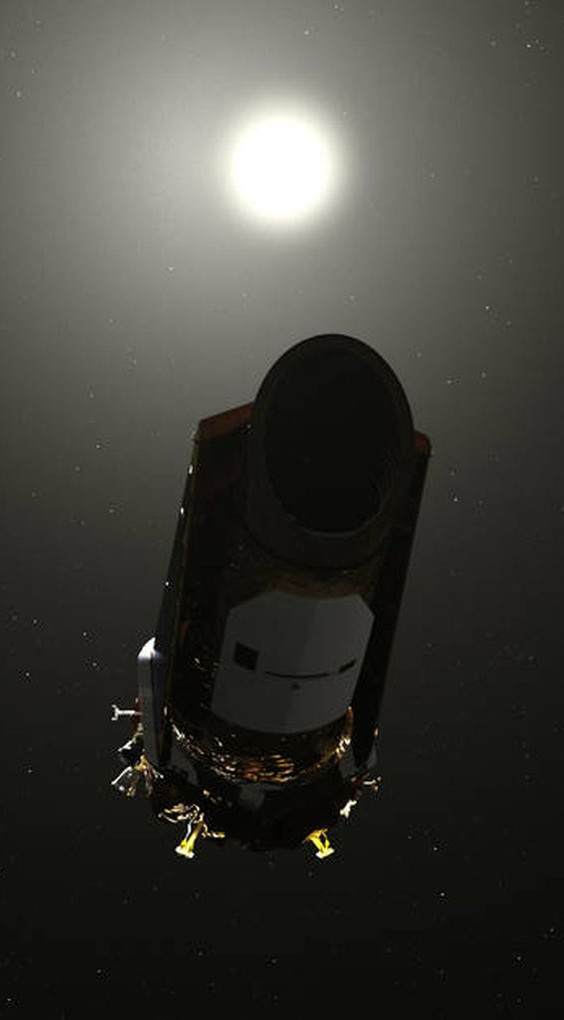

Kepler's era wraps up

NASA is preparing to send off the most prolific planet-hunting machine in history.

NASA is preparing to send off the most prolific planet-hunting machine in history.

NASA's Kepler space telescope, which discovered 70 per cent of the 3,800 confirmed alien worlds to date, has run out of fuel.

Kepler can no longer reorient itself to study space or beam data back to Earth.

“Kepler has taught us that planets are ubiquitous and incredibly diverse,” Kepler project scientist Jessie Dotson has told reporters.

“It's changed how we look at the night sky.”

Kepler’s fuel stocks have been running low for months, leading mission managers to put the spacecraft to sleep several times to extend its operational life.

Kepler's tank finally went dry two weeks ago.

“This marks the end of spacecraft operations for Kepler, and the end of the collection of science data,” says Paul Hertz, head of NASA's Astrophysics Division.

Kepler searched for alien worlds using the “transit method”; measuring dips in brightness caused by planets crossing a star's face.

Kepler started off by continuously assessing a single patch of sky, studying about 150,000 stars simultaneously.

That work yielded 2,327 confirmed exoplanet discoveries.

In May 2013, one of Kepler's four orientation-maintaining “reaction wheels” failed, which left it unable to keep itself steady enough to make the ultraprecise transit measurements.

But Kepler's handlers soon figured out a way to stabilise it using sunlight pressure, allowing it to debark on a second mission dubbed ‘K2’.

During this phase, Kepler studied a variety of cosmic objects and phenomena, from comets and asteroids in our own solar system to distant supernova explosions. K2 also uncovered 354 new planets.

Thanks to Kepler's observations it is now believed that about 20 per cent of sun-like stars in our galaxy appear to host rocky planets in the habitable zone - where liquid water could exist on a world's surface.

While its work is now over, Kepler’s impact will continue, with about 2,900 “candidate’ exoplanets detected by the spacecraft still to be studied in detail.

“It's an occasion to mark, but it's not an end,” Kepler system engineer Charlie Sobeck said.

Print

Print